A 50-year-old retiree says his ‘biggest mistake’ was saving too much in his 401(k). He explains what he would do differently and his work-around for being illiquid when he retired.

1 min readA 50-year-old retiree says his ‘biggest mistake’ was saving too much in his 401(k). He explains what he would do differently and his work-around for being illiquid when he retired.

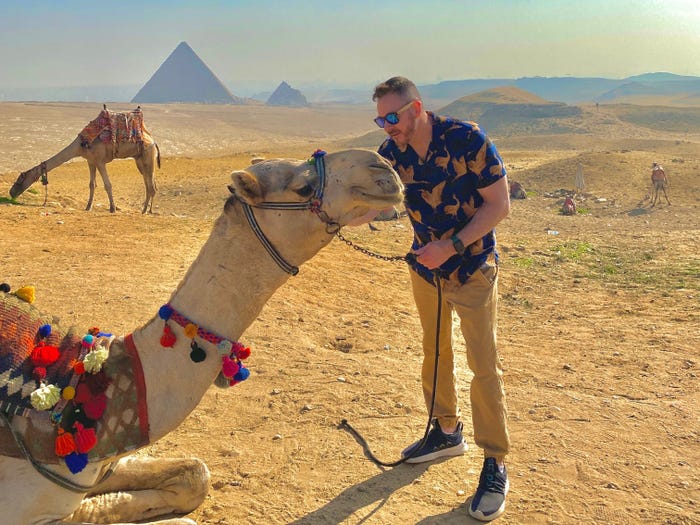

Courtesy of Eric Cooper

- Eric Cooper retired at 48 with $2.4 million in his 401(k) but lacked liquidity.

- If he could go back, he said he’d put less money in his 401(k) and more in a brokerage account.

- His work-around is an IRS rule that lets him withdraw $20,000 a year penalty-free.

In his early 20s, one of Eric Cooper’s first bosses gave him some sound money advice: Contribute as much as you can to your 401(k).

He took it to heart and maxed out his plan nearly every year of his 25-year career.

Starting early and saving consistently paid off. By the time he retired from his corporate-communications career at 48, he had $2.4 million in his 401(k) account, which Business Insider verified by looking at a copy of his retirement-savings statement.

While Cooper says that maxing out his retirement plan was “one of the smartest things I did,” he also maintains it was his “biggest mistake” because it made him highly illiquid.

“I saved so much in my 401(k), and then when it was time to retire, I didn’t have a lot in my brokerage account or anything that was easily accessible to me,” he told BI. “So, while I was rich on paper, I did not have a lot of cash on hand.”

When you contribute to retirement accounts like a 401(k) or IRA, you typically can’t tap into those funds penalty-free until after you’re 59 ½. Withdrawals before that age can incur a 10% penalty.

If he could go back, he would have decreased his 401(k) contributions to free up more cash to invest in a brokerage account, which you can withdraw from at any time without penalty.

“Even though I would take a tax hit because I’m not maxing out my 401(k), I probably should have done it just to the match and put the rest into a brokerage account,” Cooper said, referring to the 401(k) match many companies offer, which is often referred to as “free money.”

Courtesy of Eric Cooper

When he first discovered the financial independence, retire early — or FIRE — movement in 2019, he already had a big enough portfolio to stop working based on the 4% retirement-withdrawal rule. Still, Cooper says he wasn’t comfortable walking away because he was “pretty cash-poor.”

Between 2019 and 2021 — the year Cooper submitted his resignation letter — he made a few changes to his finances. He lowered his 401(k) contributions, upped his brokerage- and savings-account contributions, and picked up a part-time job as a bike technician. He wanted to pay off the mortgages on his four rental properties completely before quitting.

“Even with my large 401(k) savings, I’m not sure I would have felt comfortable retiring early had I not had those rental properties,” Cooper, who owns four long-term rentals in Louisville, Kentucky, said. “They gave me peace of mind and income as I transitioned into retirement.”

He also researched an IRS rule allowing penalty-free withdrawals from retirement accounts.

Using Rule 72(t) to withdraw $20,000 of his retirement savings a year penalty-free

Section 72(t) of the IRS code allows individuals under 59 ½ to take substantially equal periodic payments, or SEPPs, from a qualified retirement plan without incurring the penalty.

“So few people know about it, but it’s such a powerful option for those of us who have well-funded retirement plans,” Cooper said.

There are stipulations: You must take annual distributions for at least five years or until you turn 59 ½, whichever comes later. The payment amount is based on your life expectancy and calculated through three IRS-approved methods — and the account holder calculates the payment, which can be complicated.

Cooper used the single-life-expectancy table provided by the IRS, plus a 72(t) calculator, to determine his $20,000 distribution. “You have to make sure you do the calculations correctly or you could be penalized by the IRS,” he said. “So it may be worth having your accountant verify your calculations before proceeding.”

The payments are essentially fixed for five or more years and can’t be changed without incurring a penalty. And when you take your distributions, you’ll be taxed on that money depending on your current tax bracket. Another limitation is that you can no longer contribute to the account once you start withdrawing from it.

Though there are a lot of restrictions, it made sense for Cooper, who was fully committed to early retirement. He also says it will help curb his eventual tax burden when he must take required-minimum distributions, or RMDs, from his 401(k) when he turns 72.

“This is a good way to enjoy your money now and reduce the taxes you’ll pay in the future when the IRS makes you take required-minimum distributions in your 70s. At some point, we’re going to have to start spending that money, and the IRS is going to start taxing it,” he said. “The longer it’s sitting in there, the more money it’s going to generate, the more taxes you’re going to pay down the road. I’m in a lower tax bracket now, so it makes sense to spend some of it and enjoy it while I’m young enough to do so.”