Visiting the Biggest Winery in Georgia (the Red Cellar)

8 min read‘Is it a warehouse?’, I asked, trying to make sense of what I was looking at. Then I noticed the train tracks, severed at the end nearest to our feet and running off into the distance.

Imagine a winery so big, it needs its own railway station.

Producing 100 million litres of wine from 130 tonnes of grapes annually, Bolero in Gurjaani is in a league of its own. There is no other facility in Georgia that even comes close in terms of output or physical footprint.

While I normally advocate visiting small family wineries, there was no way I could pass up an opportunity to see inside the country’s biggest commercial wine factory. Especially knowing that its history goes back to 1929, just seven years after the Red Army marched into Georgia.

It is older than the Zestafoni Ferroalloy Plant (founded in 1933), which I had the privilege of visiting a couple of years ago – and like that factory, it has been working without pause, I am told, from its inauguration until today.

This blog is not about the contemporary wine company or its owners. And it’s not really about wine, either. It is about the factory itself and its incredible story.

Bolero is not normally open to the public. I am extremely grateful to the staff of Visit Gurjaani and Gurjaani City Hall who helped to coordinate my visit. It was hands down the best wine tour I have ever done – and it’s probably up there with my top 10 most memorable experiences in Georgia.

Even though my experience can’t easily be replicated, I still wanted to share my impressions and give you a taste of what Georgia’s biggest winery looks, smells and feels like.

Bolero does have plans to launch a museum in the future – I sincerely hope they open the gates to the public. I will keep this guide updated with all the details as information becomes available.

Please note: This post contains affiliate links, meaning I may earn a commission if you make a purchase by clicking a link (at no extra cost to you). Learn more.

About Bolero

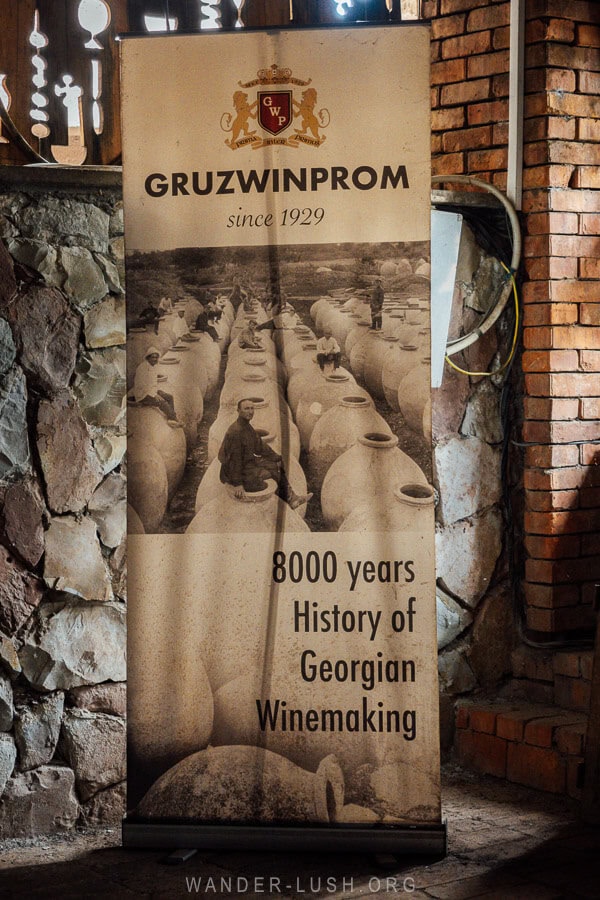

Bolero & Company (as in the Spanish dance – a name chosen by the director as something snappy and comprehensible to the European market) was founded in 2012. It is a holding firm for several companies including Universal Spirits and Gruzwinprom. For ease, I refer to both the company and winery as ‘Bolero’.

Bolero has half a dozen factories in Kakheti, the largest of which (the one I visited) is located in Gurjaani.

Sourcing grapes from its own vineyards and buying from local farmers, it produces both Georgian-style qvevri wines and European wines. These include popular varieties (Kindzmarauli, Saperavi, Tvishi) and wines made from rare and endangered species. Much of the wine is exported to Russia, Ukraine, China, Kazakhstan, France, Spain, and other European countries.

The Gurjaani facility was established in 1929, which means it is likely the oldest commercial wine factory in the country that is still operating today. Wine Factory N1 in Tbilisi was established much earlier, in 1894-96, but is no longer used to produce wine.

Today, Bolero has 200 permanent staff. The workforce swells to more than double that during the Rtveli vintage, when it’s all hands on deck to pick and process the harvest.

Rarely do wine and Soviet history dovetail in Georgia. But this is exactly the period of time that Bolero speaks to. It represents the collectivisation and centralisation of the Kakheti wine industry under communism. Not only was it the main wine-making facility in Georgia, Bolero was also the control tower from which grape imports and factory production across Kakheti region were coordinated.

All the ebbs and flows of the history of Georgian wine – from small family maranis and traditional methods to industrialisation to a focus on European exports and a change of gears to natural wine – can be observed here.

Up until a few weeks ago, I had no idea that Bolero even existed. It might be the biggest and one of the oldest wineries in the country, but it is still relatively obscure. Because the factory is closed to the general public, few people have had a chance to go inside.

So it was on a cloudy spring afternoon that I arrived at Bolero’s tall brick fence, not really sure what to expect. As soon as I saw the gates adorned with Soviet-style medallions and the bronze statue at the entrance (a close match to the lions that stand guard at the ends of Galaktion Bridge in Tbilisi), I knew we were in for something special.

The Red Cellar

Mamuka, the Director of Gruzwinprom, was there to greet us at the entrance. Soon after we were joined by Kote, our guide for the day.

We started in the heart of the winery, the oldest part of the vast complex whose full scale is impossible to grasp from the outside or from ground level within.

Covered with a wooden roof, the huge brick cellar felt draughty and dark when we wandered in. Light trickled down from a void between the walls and the rafters, and from decorative cut-outs in the wood panels along one wall.

We carefully picked a path between the holes in the floor. This was the most qvevri I have ever seen in one place – 274 clay jars in total. They are big too, with an average volume of 2,300 litres.

Having visited qvevri workshops in the past, I was interested in the provenance of the vessels. My first question to Mamuka was where were these qvevri built?

His answer floored me. Imereti, Kakheti, Guria – all over Georgia, he said. These qvevri were not custom-made for this marani as I had assumed – rather they were relocated here from different regions.

To understand why, you have to go back to the first days of the winery. Then called Tsiteli Marani (literally the ‘Red Cellar’), this facility was founded on the heels of the October Revolution, just a few years after Georgia was subsumed into the Soviet Union.

Every single one of these clay vessels was confiscated from an independent winemaker, brought to this place as part of an effort to collectivise winemaking.

I have met enough winemakers to know that a good qvevri is a very special thing. These vessels carry the weight of Georgia’s 8,000-year-old heritage of viniculture – they are critical to the wine-making process, artisanally made, and not to mention expensive.

Imagine being forced to hand your precious qvevri, and thus your entire livelihood, over to the state.

After four years in Georgia, I have seen and heard some pretty shocking things related to the Soviet period. But for whatever reason, this hit me particularly hard.

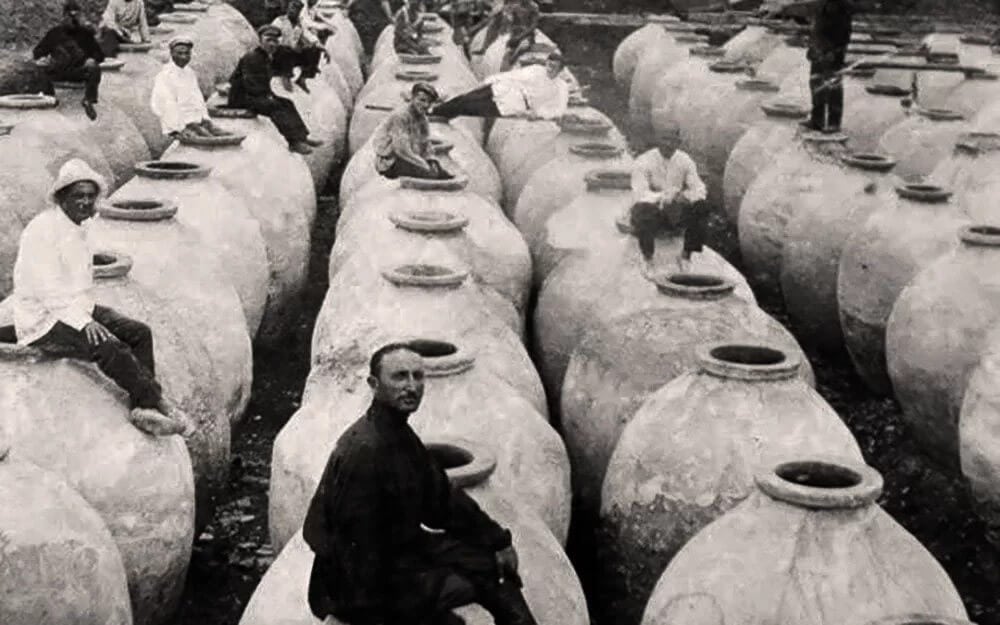

In the weeks prior to my visit, a black-and-white photo had been doing the rounds on social media. I must have audibly gasped when I saw the same image blown up on a banner standing at the back of the cellar.

It shows a dozen men sitting, standing and lounging atop a field of massive clay qvevri, each one held upright by having its curved bottom sunk into the earth.

I had assumed that the image depicted a qvevri workshop – but no, it turns out it was taken at a winery. This winery. This room.

It shows the Red Cellar in its earliest days, after the 274 confiscated qvevri had been arranged into neat rows and just before they were buried up to their necks.

Given their age, I was surprised to learn that many of the old qvevri are still in use today.

The Factory

Leaving the Red Cellar and its ghosts behind, we made our way into the ‘newer’ part of the factory, a set of Soviet-style built in the 1940s. Kote led us up a gentle ramp into one of the factory halls, and at the entrance I was surprised to see a pair of relief sculptures standing guard.

We headed up a staircase that looked just like my old apartment stairwell in Kutaisi – same unadorned metal bannisters and same small tiles on the landings – and discovered two more floors laid out identically with more towering vats.

From the rooftop, we could survey the entire factory (well, most of it) and finally get a sense for the scale of Bolero’s operation.

The Railway Station

Next, we ventured outside for a walk around the grounds. The decorations are suitably gaudy for a factory that only deals in superlatives – including a fountain with a giant replica of the famous Neolithic wine vessel unearthed in Southern Georgia.

Soon we arrived at the railway station. After spotting the tracks and figuring out its function, the rest of the one-storey building started fitting into place.

A sheltered platform extends along the side of the building, decorated with a magnificent Soviet-style panel showing a couple walking amongst grape vines and qvevri.

En route down to the platform, we passed a row of excavated qvevri with their limestone casings still on lined up alongside the tracks, more silver vats looming in the distance.

Erected to carry wine directly out of the factory in preparation for export, the freight railroad is apparently still in use today (passenger trains to Kakheti ceased many moons ago).

Our route was supposed to lead through one of the arched doors on the platform down into the belly of the factory – but finding the gates locked, Kote led us back through the grounds to find an alternative path.

The Spirit Reserve

After another lap of the factory, we reached our final stop, the Spirit Reserve. This is possibly the most impressive part of the entire operation.

Set across three or four subterranean levels, the Reserve contains 40,000 French oak barrels, every single one of which is full of brandy or cognac. The owners are so certain of this, there is a standing 10,000 USD reward on offer for any staff member who manages to find one that is empty.

All ragged concrete and barred doors, the Spirit Reserve looks and feels like a nuclear bunker. Or maybe an underground prison. I have been inside similar cellars, including at the Tsinandali Estate in nearby Telavi, but Bolero’s feels altogether more menacing. Maybe because of its sheer size.

Like the Khareba Wine Tunnel across the valley in Kvareli, the temperature down here is a constant 14-16 degrees Celsius.

First, Kote showed us the enoteca, where one bottle from every single vintage – starting from 1929 – is stored. Then we walked for what felt like hours past row upon row of oak barrels. Bolero ages its spirits for 12 years on average, but some of the barrels are 90 years old.

Finally the claustrophobic tunnels opened up a little, and some precious daylight filtered in through small windows.

We found ourselves in a tasting room of sorts. Kote opened one of the barrels and using the glass pipette he had been using to gesticulate to different points of interest on our tour, he drew out some of the amber liquid. He deposited it into five glasses and very graciously raised a toast to us, his guests.